Viva la revolución!

But there’s more than one revolution going on in my life, and looking back on it I’m not sure which is the most important. Because the other revolution is – food.

As a young child I’m nicknamed ‘The Dustbin’ because I polish off everyone else’s leftovers. I’m always hungry.

‘Ah’m ’ungry!’

My mum makes no claims to be cordon bleu – the accepted epitome of gastronomy at the time – though Aunty Margaret has done the course and can make a baked Alaska. No, we’re eating the staple foods of the sixties: bread and jam, stew and dumplings, egg and chips. Mum has a chip pan full of beef dripping. When not in use it’s kept in a cool cupboard where the fat congeals into a hard white block. I love watching the ‘iceberg’ melt as she heats it up on the stove. Very occasionally we have a roast on Sundays, it’s always cooked well done, the beautiful piece of silverside shrinking from a vibrant, bloody thing of wonder to a small block of dense grey meat, like a model of a black hole.

Vegetables are boiled. Boiled. Really boiled. One Christmas morning we go to pick up Grandma Sturgeon to bring her back for Christmas dinner. Her little bungalow stinks of boiling cabbage.

‘I thought you were never coming,’ she says.

Of course she knew we were coming, she’s just playing the martyr to get at my mum – a long-running battle to pay her back for constantly going abroad – and there’s nothing else cooking, no turkey, no spuds, just the pan of cabbage angrily boiling away. It’s only 10 a.m., and once you look beyond the tragic passive-aggression the implication is that she was going to cook that cabbage for three hours. This is what we think of vegetables in the early sixties. Cabbage must have no bite whatsoever. No butter, no oil. No condiments besides salt and white pepper, no mustard, no horseradish, and packet gravy. I’m not complaining, I love it. I lick everyone’s plate clean. And on high days and holidays we have sherry trifle to follow.

School meals really lower the bar: a strange concoction they call ‘curry’ – mince in a flavourless slurry with sultanas, which expand into tiny footballs as they heat up and burst in your mouth; liver that’s mostly tubes and gristle (‘boingy schnozzle’ my friend Troy calls it), the knives are never sharp enough to do the requisite surgery; and the pièce de résistance – boiled tinned tomatoes on toast. It always looks like a mistake, but it comes round once a fortnight.

The attitude to food at school is epitomized by one of the regular punishments, which is simply called ‘toast’. If your name-tagged gym shorts are found outside your personal clothes locker, if the hospital tucks on your bed aren’t quite crisp enough, if your tie is considered too loose or your shoes not shiny enough, you will be punished with ‘toast’.

Toast involves getting up at least an hour and a half earlier than everyone else and reporting for duty in the kitchen, where Mrs Semple will be congealing some eggs or killing some beans. There’s a giant grill which holds ten slices of bread at a time, and your job is to make 240 rounds of toast. Ten slices for each of the twenty-four tables. The grill only does one side at a time so this involves loading the grill forty-eight times.

As we all know, toast sweats, and any toast made an hour and a half ahead of time and piled on a plate is doomed to become a tower of sogginess – this is the plate for the table of your worst enemy, so at least there is some benefit to doing ‘toast’. The other benefit is that your table will get the best toast: it will be the last to be made and will be beautifully crisp and dry. The secret to the ultimate toast is to stack it like a house of cards on the vents above the grill.

It’s important to provide the top table – the one with the masters and prefects – with good toast too. Because you can be punished with ‘toast’ for not making sufficiently good enough toast.

University in Manchester doesn’t seem much better. Food becomes a game: there’s a curry house called the Plaza behind the medical school where if you drink a pint of their ‘suicide’ sauce you get your whole meal for free – many try, few succeed.

The Danish Food Centre is an all-you-can-eat buffet of cold meats and pickled herring. Of course with my Danish heritage I feel right at home but we have more of a ‘Roman’ attitude to it – regularly eating a week’s worth of food in a single sitting until we’re banned.

There’s a new-fangled ‘vegetarian’ cafe called On the Eighth Day on the Oxford Road, serving massive bowlfuls of pulses with rice; it’s fairly bland, but very cheap, and fills you up. Then empties you out.

But everything changes when I get to Soho. Many people think of it as the centre of the sex industry, or the film industry, but really, in 1980 it’s the centre of Italian food in Britain.

Only about twenty years previously Panorama played an April Fool’s Day prank on the viewing public by filming ‘the spaghetti harvest’, which showed them pulling strands of spaghetti from spaghetti trees. I remember watching a repeat of it as a young child and finding no reason to disbelieve them, because as far as I know pasta only comes in two forms – spaghetti hoops or alphabetti spaghetti.

But here are shops – Lina Stores on Brewer Street, Camisa & Son on Old Compton Street – selling all sorts of ‘pasta’, dry and fresh, some filled with delicious parcels of spinach and ricotta, some infused with truffle oil. Truffle! What’s that? Even the jars of pesto are exotic, to say nothing of Parma ham, bresaola, parmesan cheese, tomatoes that taste of something, fresh basil, black pepper. Black! Great chunks of it, not the grey powder I’m used to.

There are vegetables in Berwick Street market I’ve never seen in the flesh before – aubergine, courgette, artichoke, and garlic for heaven’s sake – my mum still hasn’t cooked with garlic.

And the coffee in Bar Italia – espresso in tiny little cups like ceramic jewels; dark, bitter yet sweet, with that crema of ultra-fine bubbles on top. It seems from a different food source altogether to the instant coffee I’ve had up until now, which tastes of wet cardboard and smells like dog’s breath.

Olives! Salami! I would argue that the revolution from cheese and pineapple on a stick to olives and salami is far greater than the revolution from The Good Life to The Young Ones.

Rik and I often go to a little Italian restaurant round the corner from the Comic Strip Club, called La Perla. It feels like it’s been transported straight from the back streets of Milan – an old-fashioned Italian with the kind of elderly waiters that simply don’t exist any more. They wear ties and waistcoats and have aprons round their waists, and they take great pride in their job, treating it as a career, not something to do while waiting for something better to turn up.

The place is actually fairly cheap but it feels expensive: polished wood and heavy white linen tablecloths, with an old-fashioned sweet trolley lurking in the shadows. And the beauty of it is, that because we belong round these parts, we go often enough for the waiters to recognize us, and as we walk through the door they smile and shout to the kitchen, ‘Fegato per due!’ because that’s what we always have. Calves’ liver and onions on mashed potato, with spinach on the side. The perfect hangover cure. Liver that’s unrecognizable from the boingy schnozzle of our past – soft, thin and unctuous, with a sauce made from garlic, pancetta, sage and the finest beef stock, a pillow of fluffy creamed potatoes and a side order of mineral-flavoured, al dente, buttery spinach.

Viva la revolución! As Che would say.

My whole way of life is going through a revolution at this point – for instance, I’ve never been touring before.

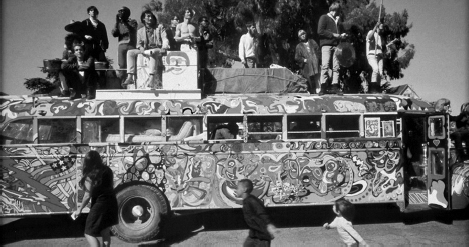

Tom Wolfe quotes Ken Kesey saying, ‘You’re either on the bus or off the bus,’ in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, a book that documents the birth of the counterculture in sixties America and its experiments with LSD. The phrase has several meanings: it’s a metaphor for being ‘with it’; it denotes a level of commitment; it can mean you’re either in tune with everyone else, or not in tune with everyone else; and, as they’re touring America in an actual bus at the time, it’s a fair description of their physical reality.

And the physical reality of being on a bus is something I come to know quite well during thirty-five years of regular touring.

My first tour is with this group of comedians from the Comic Strip Club in 1980, and it’s a blast. We’ve been working together at the club for the last year, but here we are out on an adventure. We’re going round Britain on a bus. Everything is new.

And this first tour spoils us.

The bus is very swish and has separate areas – tables with bench seats at the front, kitcheny/toilet area in the middle, and a lounge area at the back with swivelling chairs. It’s hardly rock ’n’ roll – or maybe it is – who are we to know? Though all the stereotypes in films suggest touring is fairly sleazy – a wild smorgasbord of sex and drugs. We drink a lot of cheap lager, but we also enjoy much simpler pleasures. And it’s the nicest bus we ever get. If we’d known we were starting at the top . . .

I am the chief inventor of games. I invent a game called ‘one leg’, in which the contestant, whilst the bus is in motion, has to stand on one leg without holding on to any part of the bus for as long as they can. Sudden braking can lead to instant death, which is the thrill of the thing.

Another is ‘boring but true’, in which you have to tell a true story that sounds like it’s going to be really interesting but ends up being spectacularly dull. I win with a story about motorbiking to Bradford in the snow and my gear lever falling off as I leave the M62; I know that the bike is stuck in a high gear, and that the engine will stall if I let go of the clutch, and that I won’t be able to start it again. So, I determine to ‘walk’ the bike up the hard shoulder, clutch lever squeezed tight, engine revving, all the way up the M606 to the Staithgate roundabout, where a downhill slope will aid me in setting off once more. But, after laboriously pushing it for a mile up the steep hill through a bitter snowstorm, I find that the topography after the roundabout is not as downhill as I’d remembered; if anything it’s still vaguely uphill, level at best – there’s no way that I can run the bike up to 40mph and jump on, so I simply let the clutch out and let it stall.

See what I mean? Gold medal. Feel free to play this at home.

In another, we colour our faces using Smarties and have to walk around a motorway service station.

All excessively juvenile games but they express our childish delight in what we’re doing. It’s the days before mobile phones and we have to entertain ourselves and each other. We talk a lot. We laugh a lot. I sit next to Jennifer a lot.

Our tour manager is a large man with an aluminium attaché case. He is not a people person, which you would imagine to be a requirement of the job, no, he is permanently angry and treats us like prisoners on day release. When Alexei doesn’t make the bus in time after the gig in Norwich he decides to leave him behind to ‘teach him a lesson’. He never lets go of the aluminium case and we decide it must contain either drugs, money, or the body parts of the previous act he was tour managing. Possibly all three. But he can’t break our propensity to find fun in everything. And he withdraws into his angry little shell as it dawns on him that he himself has become a figure of fun.

It’s the first time I ever stay in a hotel – it’s the County Hotel in Sheffield and it’s a dump, which I can say without fear of litigation as it no longer exists. The walls are so thin I can hear everything that happens in the room next door. I feel like Paul Simon singing ‘Duncan’ – they go at it all night long: noises, cries, slaps, occasional whimpering and the sounds of furniture being moved. I try to make out the couple at breakfast the next morning but without success. Perhaps it’s the lone businessman?

Simply visiting all the different venues is a thrill first time round. We don’t tour our own sound equipment, we use whatever is there. The equipment at Leeds City Varieties is particularly ancient and the microphone has a strange triangular brace around it rather in the shape of an arrow. I don’t know this and as Rik shouts, ‘And this is Sir Adrian Dangerous!’ I rush forward and headbutt the mic but it doesn’t fly off the mic stand as usual, it sticks into my forehead, and I look like a Dalek for a short while before I manage to pull it out.

We take this tour to Australia and have the time of our lives. The gigs go well in Adelaide, where we’re on as part of a festival. We’re in a posh hotel and rubbing shoulders with ‘famous’ people like jazz pianist Keith Tippett, smooth jazz guitarist George Benson and total icon Joan Armatrading. We’re slightly overexcited, and spotting an untouched slice of melon on Keith’s tray as he leaves the poolside, I finish it off for him. Yes, I have eaten Keith’s melon. Who’s sorry now, Mr Careers Master?

We’re feeling proud and cocky.

I’m wearing my green and black striped trousers walking down the pavement when a passing police car stops and winds down a window.

‘Hey mate, why are you wearing your pyjamas?’ asks the copper.

‘It’s all right,’ I say. ‘I’m from England, I’m a guerrilla of new wave humour, and I’m allowed to wear what I like.’